New Projections Show That South Florida Is In For Even More Sea Level Rise

Miami Herald

December

The timeline for South Florida to prepare for sea level rise just sped up a little. New projections show the region is in for higher seas, faster.

The latest predictions aren’t catastrophically different than previous years — unless your yard is already flooding a couple times a year from the steadily encroaching seas. In that case, a few inches a few years early is pretty important.

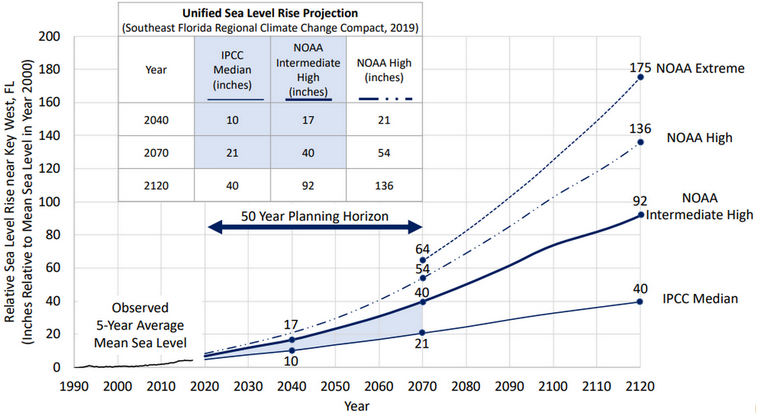

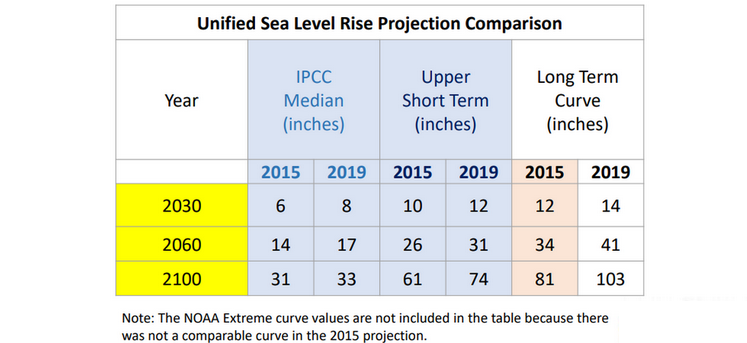

The sea rise curves unveiled Wednesday at the Southeast Florida Climate Leadership Summit in Key West tack on about three to five extra inches by 2060, and that number only gets bigger in the future.

The region went from expecting between 14 and 26 inches of sea level rise by 2060 — commonly shortened to two feet by 2060 by local leaders — to predicting 17 to 31 inches of sea rise.

“These numbers are all big enough that you can see that South Florida gets in big trouble quickly,” said Harold Wanless, a University of Miami professor of geology and member of the projections team. “If you look out the window, like the areas in the Keys that are flooding for weeks on end, this is not something that might happen, this is something that is already happening. “

These new numbers come from a group of more than a dozen scientists, researchers and local government staffers from South Florida as an update to 2015 predictions. Representatives from NOAA and The U.S. Department of the Interior were also included, but the group clarified their involvement “does not necessarily imply official review or opinions of their agencies.”

Unlike the stream of predictions for sea level rise that make headlines throughout the year, these numbers actually make a difference in South Florida. Local governments, including Miami-Dade and Miami, use them to decide how high to build new buildings.

The unified projection suggests local governments build between a range of heights, with critical infrastructure like hospitals and power stations tending toward the higher end of the range.

Susanne Torriente, Miami Beach’s Chief Resilience Officer, said her city adopted the projections in 2016.

“I recommend that the city again adopted the updated projections for planning purposes to inform all design and construction —whether designed in house or by consultants,” she wrote in an email.

Jayantha Obeysekera, head of Florida International University’s Sea Level Solutions Center and one of the scientists on the team, said the researchers analyzed all the recent research out there on sea rise before deciding which projections to include.

The ones that made the cut were the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s median curve, a conservative prediction that runs lower, NOAA’s intermediate high, high and extreme curves. They all have something in common: they’ve gotten higher since 2015.

“We looked at all the literature and it seemed like it’s trending at a rate higher than we’ve seen before,” Obeysekera said.

That’s mostly due to increased melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, but scientists also point to rising ocean temperatures. Hotter water takes up more space than colder water, a process known as thermal expansion.

While scientists are sure that climate change is occurring and that it’s human-caused, figuring out precisely how high sea levels will be in a given year is tough, thanks to all the factors involved.

“That’s going to be a problem forever, knowing the exact rate of rise,” said Wanless.

Jane Gilbert, Miami’s Chief Resilience Officer, said the uncertainty is why the city is designing its new stormwater masterplan system to a certain amount of inches of sea rise rather than a particular year.

“We are modeling for 18 [inches] and 30 [inches] of SLR,” she wrote in an email. “Of course, we will own the model and could run the model for different levels as well in the future.”

Wanless, who tends to predict higher rates of sea rise, worries that builders and developers will look at the multiple curves and choose the lowest one to build to, rather than some of the higher curves.

He pushed for the inclusion of NOAA’s extreme curve — one Obeysekera said is “a pretty rare scenario with a very low probability” — to show South Floridians the risk they could face if carbon dioxide emissions are allowed to continue unabated.

Of the NOAA intermediate curve, which predicts a little over three feet by 2070, he said “that’s the lowest one I would even talk about, and I think everything under that is wishful thinking.”

So do these higher numbers mean Miami-Dade leaders will start saying two and a half feet by 2060 instead of two feet? Not necessarily.

“We’re always in that posture of trying to give people some sense of the future conditions, but at the same time let the uncertainty in the data bracket that,” said James Murley, Chief Resilience Officer for Miami-Dade County.

However, Miami-Dade plans to begin updating its existing buildings soon, and Murley said this latest data would be part of that process.

“The fact that we’re always prepared to update the information and that the process of updating and building new facilities is influenced by this is one of the best parts of the collaboration,” he said. “I don’t know another place that does it like this.”

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative founded by the Miami Herald, the South Florida Sun Sentinel, The Palm Beach Post, the Orlando Sentinel, WLRN Public Media and the Tampa Bay Times.