FEMA Demands Homes That Don’t Flood. Towns Aren’t Listening.

By Christopher Flavelle and John Schwartz

WASHINGTON — It’s a simple rule, designed to protect both homeowners and taxpayers: If you want publicly subsidized flood insurance, you can’t build a home that’s likely to flood.

But local governments around the country, which are responsible for enforcing the rule, have flouted the requirements, accounting for as many as a quarter-million insurance policies in violation, according to data provided to The New York Times by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which runs the flood insurance program. Those structures accounted for more than $1 billion in flood claims during the past decade, the data show.

That toll is likely to increase as climate change makes flooding more frequent and intense.

Local governments are responsible for enforcing the requirements, but almost none have been penalized for failing to do so. “There’s no negative consequences for violating the rules,” said Rob Moore, a senior policy analyst with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Rachel Sears, director of FEMA’s floodplain management division, said her office’s strategy was to avoid “immediately pursuing” penalties, and to instead encourage towns and cities to do better. “We work with the communities and property owners to directly remedy the specific violations,” she said.

The National Flood Insurance Program covers homeowners in flood-prone towns and cities, often at rates below what private insurers charge, if they offer it at all. In return, FEMA requires local officials to ensure that the ground floor of every new or repaired building is at least as high as the expected peak of a major flood.

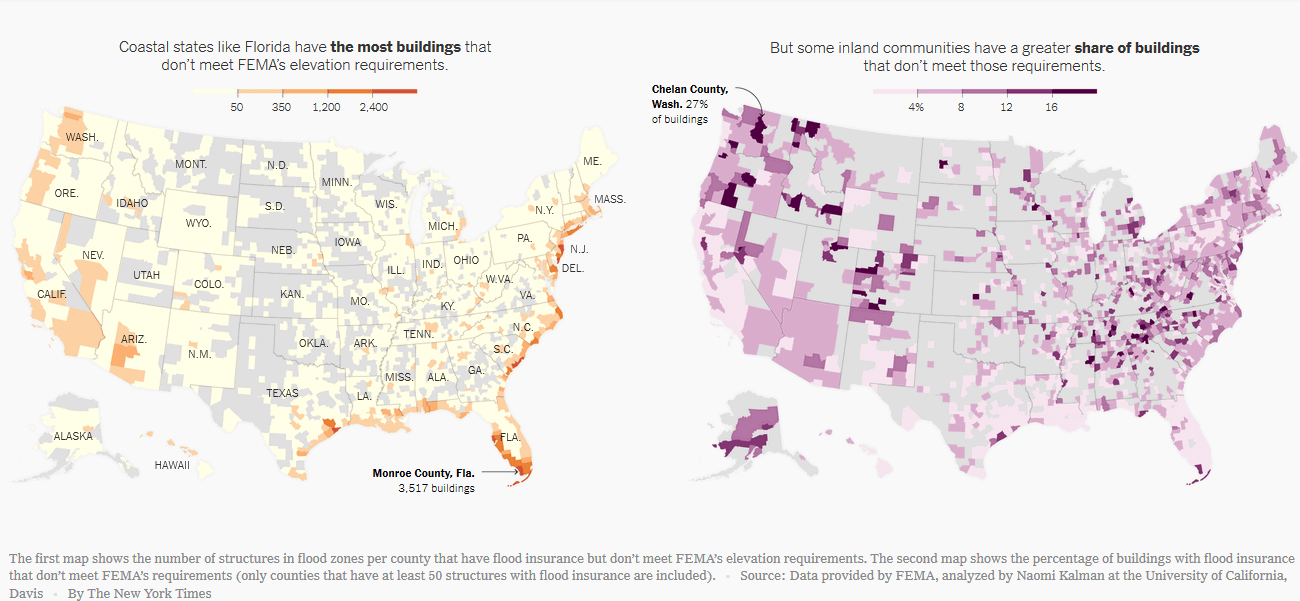

Yet as many as 112,480 structures nationwide fail that test despite being built after the rules took effect, typically decades ago, according to FEMA data analyzed for The Times by Naomi Kalman, a geographic information specialist at the University of California, Davis, and her colleagues. Those structures account for 249,049 flood insurance policies, each representing a separate household or business. (Some buildings, like condominiums, have several units.)

More than 2,000 counties nationwide have buildings on the list. The greatest numbers are in Ocean County, N.J.; Pinellas County and Monroe County, both in Florida; Charleston County, S.C.; and Galveston County, Texas. Each has more than 3,000 structures with ground floors that are too low, despite being built after the rules took effect. Another 18 counties have at least 1,000 structures that are listed as being in violation of the rule.

Taken together, the owners filed 29,639 flood insurance claims between 2009 and 2018. Those claims led to federal payouts of more than $1 billion, an average of $34,940 per claim.

It’s not just a coastal problem. Many counties with a high share of properties are well inland, a reminder that flooding is a nationwide threat.

FEMA said some of the properties on its list were probably incorrectly categorized, though it doesn’t know which ones or how many. For example, local building inspectors might have recorded a ground floor as lower than it actually is. Or a home might have been outside the flood zone when first built, but the zone later expanded.

“Not all minus-rated policies represent a failure to comply with local floodplain ordinances,” Ms. Sears said, using FEMA’s term for properties that are too low.

The only way FEMA can verify which places are breaking its rules, and why, is to conduct a local audit. Of the more than 22,000 communities that participate in the insurance program, FEMA audited just 610 last year, or fewer than 3 percent, according to the agency. That’s down from about 1,500 a year in the early 1990s.

“Every federal program has to use the resources available to them,” Ms. Sears said. “We have a set budget.”

Roy Wright, who ran the insurance program until 2018, offered another explanation: FEMA is hesitant to enforce its own rules because its only enforcement tools are so severe. In short, punishment can make the homes all but unsellable.

The first punishment is to put a city or town on probation, a step that entails a $50 annual surcharge on insurance policies.

But the next step is the big one: suspension. That amounts to expulsion from the program — preventing homeowners or businesses from getting federal flood insurance. Without flood insurance, a homeowner in a floodplain can’t obtain a federally backed mortgage, which is what can make a property hard to sell.

Throwing a community off the program also means people would lose a valuable tool for rebuilding after a flood. And that would make the other part of FEMA’s job, helping communities recover from disasters, even harder.

“People aren’t in a hurry to suspend an entire community, and make flood insurance unavailable to all of them, if only 1 percent of them are bad actors,” said Mr. Wright, who now runs the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, an industry-funded research group. Even if FEMA did want to jettison a community for breaking the rules, it would prompt hard questions from its representatives in Congress, he added.

But letting communities off the hook for breaking the rules sends a signal to other officials around the country that they can follow suit, said Chad Berginnis, head of the Association of State Floodplain Managers. Other towns might decide, “FEMA didn’t do anything” when other cities didn’t enforce the rules, Mr. Berginnis said.

In the five decades since the program was started, only 77 communities had been put on probation as of last November, according to FEMA. Only 12 have been suspended for failing to enforce the rules.

Ms. Sears said communities that fail to enforce the minimum-elevation rules are already penalized, because homeowners in those structures have to pay higher insurance premiums. “These premiums can be quite high,” she said. “The individual policyholder, not the taxpayer or the NFIP, pays for this additional risk.”

And throwing communities off the program won’t reduce that risk, Ms. Sears said. “The goal is not to remove communities,” Ms. Sears said. “Our goal is to make sure that they’re enforcing the requirements.”

In interviews, officials from places nationwide that have run afoul of the requirements defended themselves, describing the myriad ways a community can end up on the wrong side of FEMA’s rules.

In Kirkland, Ill., Ryan Block, the village president, said a resident in the 1990s who owned marshland filled it in to build houses, ignoring warnings from FEMA and state officials. “They continued to build homes until the subdivision was basically done,” Mr. Block said.

FEMA spent more than 20 years warning Kirkland to fix the problem, Mr. Block said, before putting the village on probation in 2016. He said he doesn’t know why the agency waited so long to act, but once it did, local officials began making the fixes that FEMA requested, spending $600,000 to restore the wetlands.

Other places have faced no consequences. In many cases, local officials reported having never even been told by FEMA that they were doing something wrong.

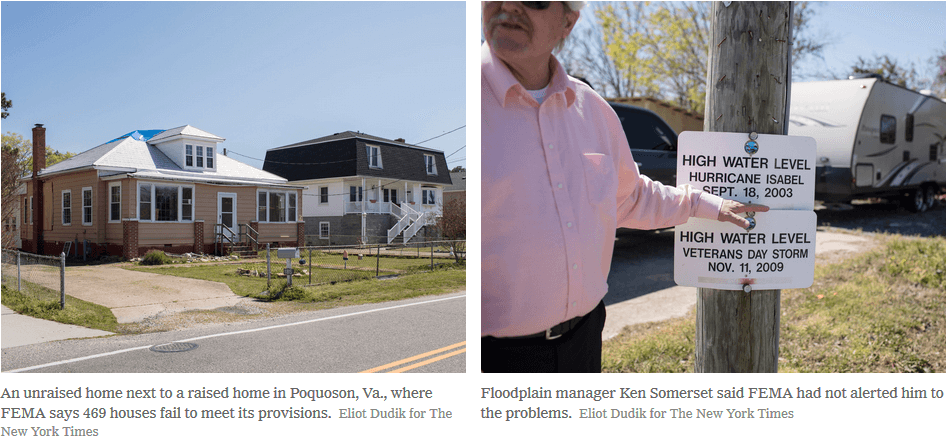

In Chesapeake, Va., which, according to FEMA’s data, has 650 structures built below the flood level, permit director Jay Tate said he didn’t know which homes were in violation of the rules. He said the city joined the program in the late 1970s, but didn’t start enforcing the rules for perhaps a decade or more. “It probably wasn’t until about 1990 that we had a robust review of building plans to make sure it was in accordance with that,” Mr. Tate said.

In nearby Poquoson, Va., which FEMA shows as having 469 homes that fail to meet its provisions, about 10 percent of all homes in the city, floodplain manager Ken Somerset said the agency hadn’t alerted him to the issue. “I would be interested to see that list,” Mr. Somerset said.

In Pinellas County, Fla., which has almost 4,000 structures that are too low, floodplain manager Lisa Foster said there were different possible explanations, including inaccurate elevation measurements. She said the county would have no way of knowing how many structures were built in violation of the rules “without doing a detailed analysis of the data for each,” and said she wasn’t aware of FEMA contacting the county about the problem.

“Pinellas County has a very active floodplain management program,” Ms. Foster said in a statement.

In the Florida Keys, Christine Hurley, assistant administrator for Monroe County, likewise said she had no knowledge of FEMA warning officials about the county’s more than 3,000 structures that are too low.

One of the counties with the greatest number of affected properties in the country is Cape May, N. J., where FEMA data says 3,308 structures are too low. When asked about the figures, Martin Pagliughi, the county’s emergency management director, said he had never heard the term “minus-rated” that FEMA uses to describe structures that are too low.

When told what it meant, he said FEMA must be wrong. “I don’t believe the numbers,” Mr. Pagliughi said. “That’s way out of whack.”

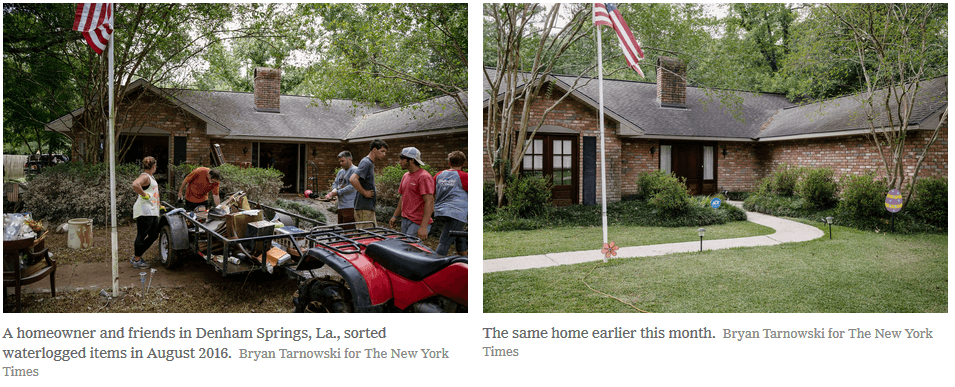

FEMA’s reluctance to impose penalties has become apparent most recently in Livingston Parish, a part of Louisiana just east of Baton Rouge that was hit hard by flooding in 2016. Thousands of homes were severely damaged.

Under the rules of the insurance program, homes that are badly damaged must be rebuilt according to the latest floodplain rules, including elevating the ground floor to at least the height of an expected flood. But more than 3,000 homes in Livingston Parish were built back to their too-low original height, according to Ms. Sears.

It’s not clear if local building inspectors gave people permission to break those rules, or simply didn’t know the rules were being broken, Ms. Sears said. Either way, FEMA is now pushing officials for a plan to get each of those homes elevated. That hasn’t happened. The chief penalty so far has been the $50 annual surcharge.

“We’re continuing to assess their status,” Ms. Sears said, when asked why the parish was still in the program. “It’s in the interest of everyone to have communities that are enforcing strong floodplain management requirements — and that we have insured survivors.”

Layton Ricks, the president of Livingston Parish, said he understood FEMA’s concerns. “I’m not stupid,” he said. And he also appreciates the work local FEMA representatives have done to help people after the floods, which left more than 80 percent of the parish under water. “My goal was to get people back in their homes,” he said.

“Did we violate some FEMA rules and regulations? I guess maybe we did,” Mr. Ricks added. “I also know what it’s like to look at that 70-, 75-, 80-year-old couple trying to get back in their homes, and they don’t give a flip about FEMA regulations.”

For more climate news sign up for the Climate Fwd: newsletter or follow @NYTClimate on Twitter.